Before you go any further, please do spend a little time with our review of the newly released Atari 2600+ console – that’ll help you get a handle on the basics of this machine, a slightly-shrunken and somewhat-modernised recreation of the 1980 CX2600-A model Atari VCS, which kept the woodgrain of the 1977 original but dropped the front-mounted switches from six to four.

Pop back here once you’re done. It’s fine, I’ll wait.

Or watch our video review of the ATARI 2600+, both are just as good!

Back? Great.

So, Atari’s hugely successful machine, the market leader by a huge margin in North America throughout the late 1970s and early ‘80s, would be renamed the 2600 in late 1982 so as to fit the convention introduced with the release of the 5200 SuperSystem (the less said about that one, the better) – and that’s the moniker that’s stuck since, hence this new model’s branding.

Speak to many a player old and young, and if they’ve any awareness of Atari’s earlier years of home-gaming activity – the company had established itself as a force in the arcades some years before the VCS’s launch – chances are they’ll talk about how iconic the 2600 was, how important it was, perhaps how it was trailblazing in a way that nothing else was at the time.

But, was it really so special?

I mean, yes, commercially, it really was. By the time of its discontinuation in 1992, some 15 years on from its launch, the VCS/2600 family of consoles had sold around 30 million units worldwide.

Compared to today’s systems that’s not a lot to get excited about – the PlayStation 4 has sold 106 million units, the Switch somewhere in the region of 132 million – but measuring it against its contemporaries shows just how dominant Atari was during the late 1970s and early ‘80s, before the North American market crashed in 1983.

Mattel’s Intellivision, launched in 1979, sold fewer than four million units. Coleco’s ColecoVision, widely regarded as technically superior to the VCS and capable of delivering near-arcade-perfect coin-op ports (its pack-in, Donkey Kong, was very close to the legendary Nintendo cabinet), managed fewer than two million sales between 1982 and ’83.

Fairchild’s Channel F – which hit stores before the VCS, in November 1976, and was the first home console to use ROM cartridges for its games – couldn’t shift 400,000 units.

The same story played out for all would-be competitors: figures for the uniquely vector-graphics-driven Vectrex system aren’t officially documented but it’s estimated that around 600,000 units were sold; and Magnavox’s successor to its genuinely ground-breaking Odyssey console of 1972, the Odyssey2 (marketed in certain territories as the Philips Odyssey 2), is thought to have peaked at around two million across its six-year lifespan of 1978 to ’84.

Atari’s profits might have dipped by over $500m in 1983 – as was the trend for all North American console manufacturers that year, leading to many selling up and/or going bust – but it still saw steady sales for its 2600, which kept creeping up by around a million units per year, globally, after the crash.

Which is to say that even with the NES and Master System available, and come the end of the decade the Mega Drive too, people were still picking up new Atari 2600s.

It was, and remains, a fantastically important piece of gaming hardware, a system that was so many people’s first experience with home consoles. But for all of its popularity, it was a system that pinched more than it pioneered.

Atari’s penchant for, ahem, borrowing from others in the gaming space began before the VCS, and even before 1972’s Pong.

The company’s founders, Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney, worked together on the first commercially viable arcade game, Computer Space, which enjoyed modest success upon its release in 1971 – at least enough to show there was a future in these stand-up, coin-operated video game things.

But this was something of a clone of a game Bushnell had played during his university years, Spacewar!, originally created in 1962 for PDP-1 minicomputers (which, to look at them today, really aren’t mini at all).

The pair’s first game under the Atari name, Pong, was also a derivative of something already playable – Bushnell copied Tennis, a game for the Magnavox Odyssey, an act which resulted in Magnavox suing Atari in 1974.

The concept for what would become the VCS didn’t even start at Atari. Okay, it did – but indirectly.

In 1973 Atari acquired Cyan Engineering, and it’s here that the idea for Atari’s home console blossomed. Employees at Cyan, notably engineers Steve Mayer and Ron Milner, were envisioning a home system based around microprocessors while Bushnell was still focused on putting Pong anywhere and everywhere.

Yes, this is a bit of a reach, but it was at Cyan – part of Atari but not Atari itself – where the then-new 8-bit 6502 microprocessor by MOS Technology was incorporated into a design which would, over several iterations and a move to the smaller 6507 chip, ultimately become the VCS.

Both the overall look of the VCS, and the design of its cartridges, were spearheaded by Gene Landrum, who was fresh from consulting with Fairchild on the Channel F. It was Landrum who had put Jerry Lawson on the Channel F project, and Lawson would ultimately lead a small team at Fairchild team to produce the world’s first ROM cartridge (but that’s a whole other story).

Further design on Atari’s carts came from ex-Fairchild employee Douglas Hardy, whose knowledge of the Channel F’s game design enabled Atari to avoid any awkward patent problems with their own ROM carts.

So, again, Atari was looking at industry precedent, and at people outside of its own company, to progress in the home console space.

Which is fair enough – you bring in the people you need to achieve the goals you have. Business 101.

But what it adds up to is the Atari VCS being a sort of magpie machine, a combination of knowhow and experience from elsewhere in the still-fledgling gaming world, which added up to something which was far from the most powerful option on the market for much of its commercial relevance, but had several killer apps in the shape of Atari’s own coin-op ports, was priced competitively, and benefitted from being exceptionally popular before technically superior alternatives arrived.

Why buy an Intellivision, or anything else, if your friends had an Atari? It makes more playground sense to get the same console as everyone else, so that games are more easily swapped and shared.

To wit, the Atari VCS didn’t do a whole lot that felt original, or inspired – it simply achieved critical mass where others didn’t, by leaning on innovations that’d come before it and adapting them for its own purposes.

In contrast, the 2600+ does feel novel, exciting, amid the modern retro console competition. As you’ll have seen or read in the review proper, this is an HD-output, USB-C-powered system that will connect perfectly to modern TVs and output at either 16:9 or (better, obviously) 4:3.

It’s a hugely convenient way to put Atari 2600 games – and 7800 titles too, due to compatibility with those releases – back into lounges and bedrooms, loft dens and man caves, without the need for chunky CRTs and fiddly analogue tuning.

And yes, other notable gaming names have done similarly in the recent past – Nintendo with its NES and SNES Classics, SEGA with its pair of mini Mega Drives, Sony with its PlayStation Classic, and more besides.

But none of those deliver what the 2600+ does – immediate compatibility with a huge array of back-catalogue and wholly corporeal game carts.

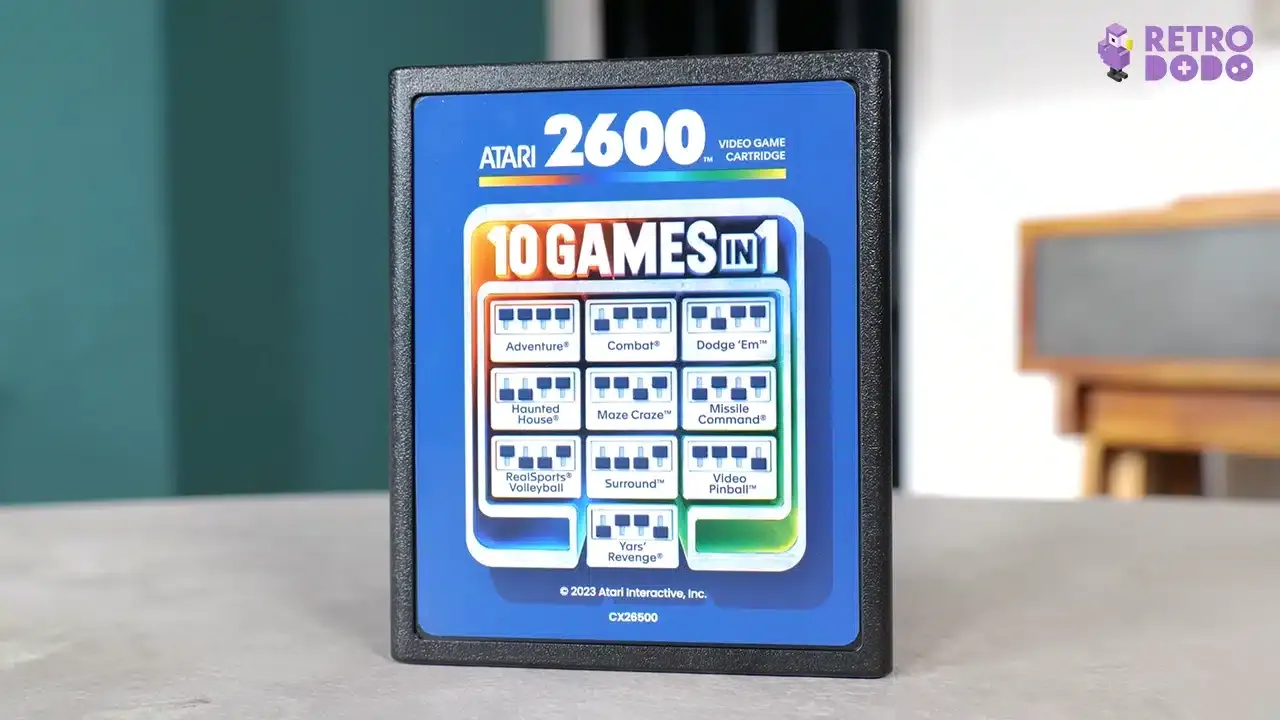

There are no built-in games inside the 2600+ – the ten games it ships with, amongst them Missile Command and Yars’ Revenge (others are available separately – again, do refer to the review), come on a cartridge and are selectable not via an on-screen menu, but by dip switches on the cart itself.

The joystick it’s bundled with, a perfect 1:1 replica of the CX40 controller introduced in 1978, has only the one fire button on it – no pause, no rewind, no options menu input to select save states or screen filters.

To turn the console on or off, to reset the games or select the game modes, you have to reach over to the console and use its period-accurate switches.

The same applies to the choice between A (advanced) and B (beginner) difficulties. This is a firmly old-school-feeling device with only slight concessions to the here and now – and it feel fantastically fresh for it.

Indeed, by having a working cartridge slot, the 2600+ is breaking new ground for these various minis and classics. (Not that this is a particularly mini machine at all – it’s roughly the size of 1986’s 2600 Jr model).

While you can hack other modern retro minis, adding more ROMs to what comes as standard, here you can experience what it was actually like to have to get up, change out a cart, flip the switches and set the modes, and sit back down again. You might not want that – but for me, it’s a routine, a ritual, which has been largely lost in modern gaming.

It adds a physicality that goes beyond just getting a new game on a disc – this is so much more hands-on, and it’s this interaction with the hardware, with the carts and the controllers (paddles are available too, so you can play the likes of Breakout and Video Olympics), which really feels pioneering within its product niche.

I’m an advocate for game preservation, and always encourage people to dig into the history of the medium where I can – gently, of course, as you don’t have to know anything about Atari, Magnavox, Epoch or Vectrex to enjoy modern PlayStation or Xbox games to the fullest.

But whereas other modern retro consoles – official ones, from the original makers I mean, rather than those made by the likes of Analogue or Hyperkin (again, that’s a whole other piece), or the compilation-centric Evercade range – scratch an itch with some essentials included out of the box, and could encourage newcomers to their libraries to delve deeper, maybe pick up a second (or third-, or fourth-hand) SNES or Mega Drive and a few game carts, the 2600+ already has that expansion potential, ready to go.

Just get on ebay, spend a few quid on Space Invaders or Alien Brigade or Ninja Golf or Asteroids, and slap that ancient piece of plastic straight into your 2023-released hardware.

It seems wild, in light of the 2600+, that neither SEGA nor Nintendo has done this yet – and no, I am not about to be dragged into discussing those AtGames ‘Mega Drives’. We’re all trying to forget them.

So yes, I’m a fan of the 2600+. Who it’s for, exactly, is less obvious than the minis from Nintendo and SEGA, both of which have games on them from series that are still going strong today and therefore their market is, basically, everyone.

Here though, absolute beginners to Atari will probably find these games incredibly primitive and likely drop them before realising several games are much deeper than their visuals suggest; while purists may baulk at how it’s using emulation software to bring these 40+ year old games back to life, rather than the FPGA approach of the premium-priced Analogues. But if you’re somewhere in between those poles?

You might also feel this is Atari setting a new standard, and not merely mimicking what’s come before it.