Gaming history is full of “what if?” moments, as so many games that seemed poised to transform the industry have flopped and faded into irrelevance within months of release. No game sums this up better than Majestic, a groundbreaking conspiracy game that failed to make an impact due to its unusual format and the situation surrounding its release. While the game is nearly forgotten today, its DNA can be seen all across the gaming industry, with many of its innovations now commonplace.

2001 was a massive year for digital entertainment and incredible video games for that matter, with many legendary, era-defining games hitting shelves. Plus, the internet’s increasing ubiquity led to gigantic changes in how people worked and played. Majestic hoped to ride this wave by combining the then-new ARG (Alternative Reality Game) genre with classic adventure game ideas.

The excitement for Majestic began several months before release, as the game’s early demos and previews got a lot of coverage in the gaming press, and the game won Best Original Game at the 2001 Game Critics Awards. EA hired the advertising firm Human to promote the game to consumers, leading to several promotional stunts that saw ‘secret agents’ take over bars and intersections to hand out magnets and subliminal message-laced CDs.

Entering The World Of Majestic

Unlike many early-2000s games, Majestic was released episodically, with a new episode landing every month. The first was released on July 24th, 2001, followed by the second episode, “Control,” on August 27th, and the third, “Visions,” on October 4th. The first season’s final episode, “Disinformation,” debuted on November 16th. While the first episode was free to download, users had to pay a monthly $10 fee to subscribe to EA’s Platinum service to play later episodes.

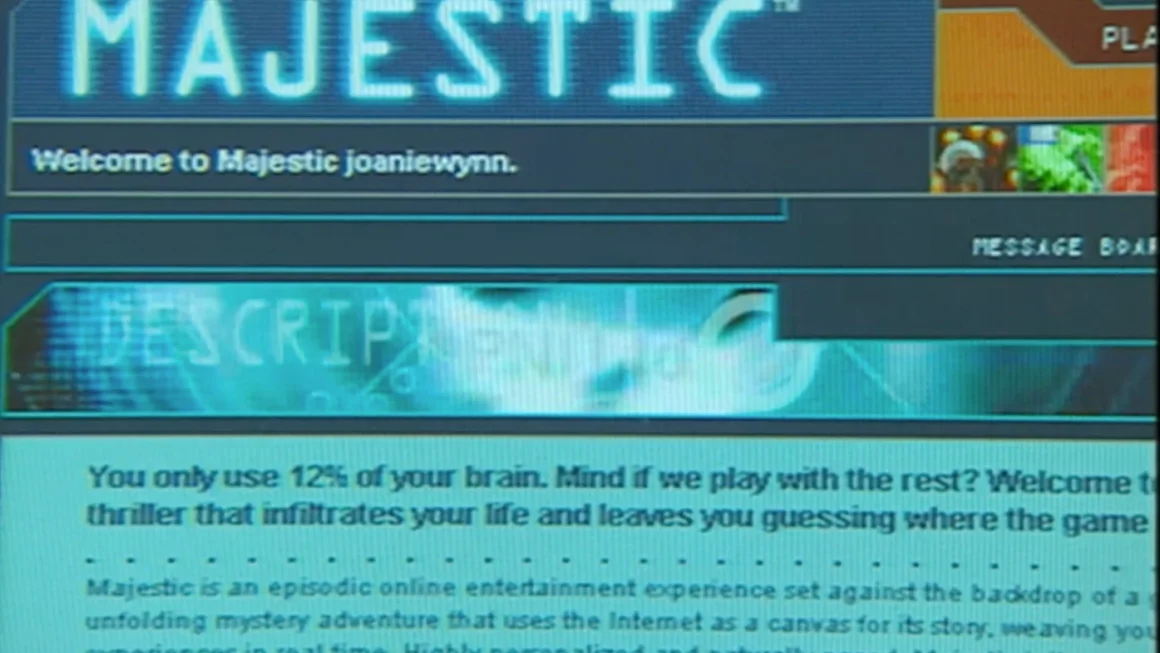

Those who dived into Majestic would quickly learn that it wasn’t a regular game. Perhaps confusingly, upon booting up the game for the first time, players were greeted with a message from EA stating that Majestic had been suspended. This suspension was because the offices of Anim-X, the game’s developer, had burned down under suspicious circumstances. The notice linked players to the website of the Portland Chronicle newspaper, which featured a news story about the fire and the investigation that was starting up.

Thankfully, there was no need for panic. Anim-X wasn’t a real game studio, and most of the staff featured in the game’s promotional materials were actors rather than real game developers. Similarly, The Portland Chronicle wasn’t a real newspaper but a carefully designed fake. It was at this point the actual premise of Majestic was revealed. While making a conspiracy-themed game called Majestic, the staff at Anim-X had accidentally uncovered something they shouldn’t have. The players and the surviving staff of Anim-X had to untangle the conspiracy before shadowy forces could shut them up for good.

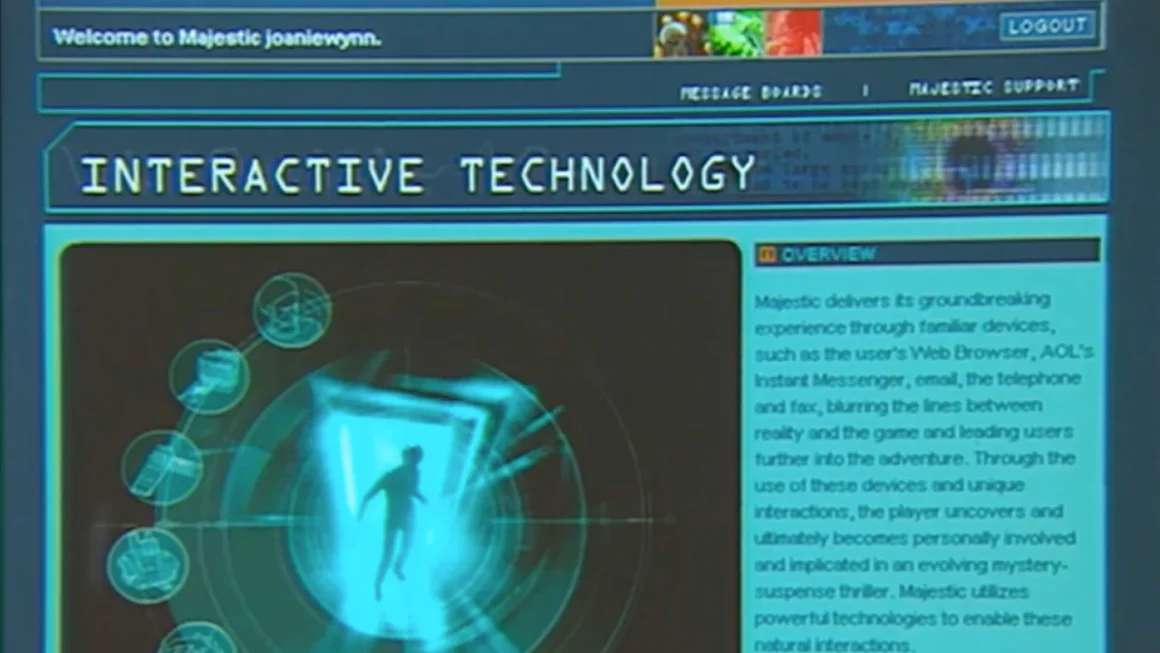

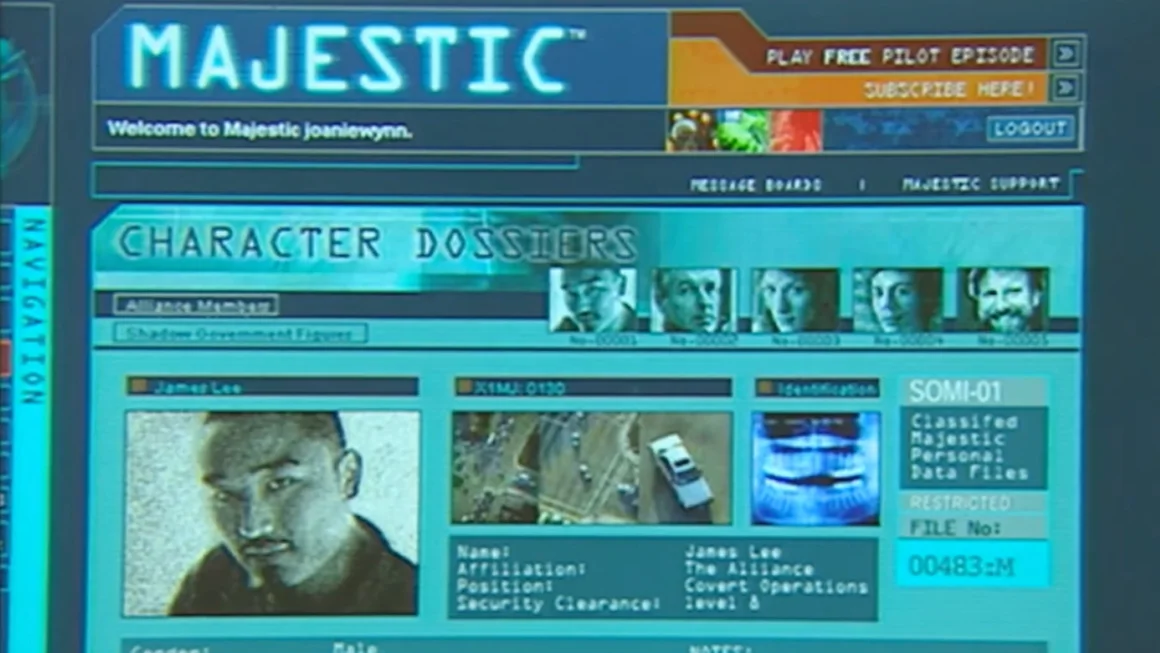

The core element of the Majestic experience was the Majestic Alliance Application, a small interface that guided players through the experience. This application contained a dedicated search engine that allowed users to search over 60 EA-created websites and a section called Allies. When a player booted up the game, the software selected several other players and some NPCs (played by bots) and added them to this section. Players could then talk to these people via the AIM instant messaging platform to get clues and collaboratively solve puzzles, adding to the immersion and giving the game a sense of community.

Majestic’s gameplay loop was simple but effective. Each section started with players getting a series of puzzles to solve. Players had to search the web, watch videos, dig into files, and manipulate websites to learn the answers. As they did this, helpful and antagonistic characters would contact players by phone, fax, e-mail, and instant messenger to further the story and give hints about the puzzles.

When the puzzles were complete, the player’s client entered standby mode, forcing them to wait until the next day to progress further. On top of this, the game operated in real-time, meaning that if a character said they were going into hiding for a week, players would have to wait a week to hear more from them.

Having the episodes consist of many small sections spread out across the month was a deliberate design choice by Neil Young, the game’s creator. He told interviewers he “wanted to create something that didn’t require you to spend hours with it each night in order to feel successful at it” because he struggled to find time for games due to his work and the impending birth of his first child.

One of the most fascinating things about Majestic was how it used pre-existing conspiracy theories and urban legends to deepen its world, expand its story, and blur the line between fiction and reality. As players experienced the story, they were frequently directed to real-world documents hosted on websites not created by EA. The firm also partnered with many pre-existing conspiracy websites, such as Conspiracy-net, a conspiracy cataloging site that had been online since 1999, including them in the Majestic Alliance Application search engine in exchange for them hosting game-relevant information. Because of this, players could easily find themselves going down conspiracy rabbit holes that were thematically linked to Majestic but not officially part of the game.

Another innovative and reality-bending element of Majestic was its embracing of user-created content. Majestic allowed players to flesh out the game’s side characters and events, and according to Neil Young, there were around 380 Majestic fan sites by August 2001. On top of this, many players decided to roleplay, remaining in character while playing the game or interacting within community spaces.

Because of this, it was hard to know where the game began and ended. This unique atmosphere famously led to Gamespy’s “Our New Office Pastime is Messin’ With the Guy Who Plays Majestic” article, which poked fun at people getting a little too immersed in Majestic’s world, leading to them thinking they were the target of an actual government conspiracy.

Thankfully, EA realized that a game that played on the boundary between fantasy and reality could cause issues, especially in the pre-social media landscape. So Majestic allowed players to tailor the experience to fit their schedules and comfort levels. Players could pick which communication methods they wanted to use, plus the times they could receive messages via these services. This way, players didn’t need to worry about getting calls while working or trying to sleep.

Digital messages were similar, as players had to be logged into the Majestic Alliance Application to get them, preventing the game from becoming too invasive. Additionally, players who shared their phone or fax machine with others could enable an option that added a disclaimer in front of every message, warning that the message was part of the game.

The End Of Majestic

However, while the game was praised for its originality, there were many complaints from both reviewers and players. A recurring criticism was that the puzzles were unnecessarily easy, and the game outright told players the solution too quickly, removing any sense of challenge. Another frequently repeated complaint concerned the game’s pacing.

While the idea of real-time gameplay captured the imagination of many, the execution struck an awkward balance. Many gamers said there wasn’t enough to do in each section, meaning they were constantly waiting for the next story moment to happen. Conversely, players who couldn’t dedicate daily time to Majestic complained that the game became hard to catch up with if they missed a few days. EA’s director of corporate communications, Jeff Brown, discussed this in a 2002 interview with the New York Times, saying:

”Players want to play at their own speed. Majestic made you play at the speed of the game, a lot of people who wanted to play were forced to wait for e-mails and phone calls.”

Plus, the game’s release method hampered it dramatically. While subscription-based episodic releases are something modern gamers have come to expect, in 2001, the concept was far from the norm. This was only intensified by the fact that pre-Majestic, nearly all ARG-style media had been free to experience, leaving fans of the genre with a sour taste in their mouths.

Majestic also was unlucky with its release date, as the September 11th attacks would occur soon after the start of the second episode. EA paused Majestic for a week on September 12th, saying: “Given the recent national tragedy, we feel that some of the fictional elements in the game may not be appropriate at this time.”

The game would resume soon after, but this break heavily damaged the game’s momentum as, in the eyes of many players, the game’s story felt a little too close to home after what had happened in real life. This is summed up best by reviewer Dan Finkelstein, who would update their review of the game with a paragraph that read:

“Majestic, which I called the game of the year one month ago, seems so incredibly dumb and stupid now, for reasons you can probably guess. Receiving personal phone calls where characters scream at you or threaten your life seemed cool a month ago. Now – well . . . it just seems scary.”

Majestic struggled to attract and maintain an audience, with its user numbers dropping constantly. While 800,000 users had registered their interest before the game’s launch, only 71,200 completed the demo episode. When presented with a paywall, most players opted to stop playing. According to Reuters, by the end of September 2001, the game’s user base had “stalled near 13,500.”

In November 2001, EA tried to boost the flagging game by releasing a physical version of Majestic. Retailing for $40, these boxed versions came with the Majestic application and a subscription for the first season. Alas, this wasn’t enough to turn the tide. In December 2001, EA confirmed that Majestic would end in the middle of 2002, and there wouldn’t be a second season. When this happened, most of Majestic’s created websites were taken down. Because of this, a good chunk of the game’s media is now lost.

In the months following the game’s closure, many autopsy pieces were written, with EA being unusually open about the situation. In March 2002, EA told the New York Times that around 15,000 people had paid to play Majestic during its lifetime. Jeff Brown didn’t sugarcoat the situation, bluntly telling the paper that “Majestic was a noble experiment that failed.”

However, it was clear that despite the failure, people believed in the project and what it represented. In a piece about the game’s cancellation, Brown told CNN Money that “maybe the consumer didn’t get it” before noting that:

“In five years, everyone’s going to be making games based on this engine. I’m not apologizing for anything!”

Looking at Majestic with modern eyes, it’s clear that Jeff Brown was totally correct, as many of Majestic’s ideas are commonplace in today’s game industry. Most obviously, immersive, interactive movies have grown dramatically in popularity and execution, with titles like Immortality and Her Story winning awards for their takes on the concept. Plus, while players in 2001 balked at the idea of a subscription-based online game, the concept would soon enter the mainstream when World Of Warcraft launched in 2004, heralding the start of the MMO boom. The same is true of Majestic’s gameplay structure as while the idea of a game you play for a short period every day didn’t resonate with gamers in 2001, today, it is the standard for live service and mobile games, with a “Daily Login Bonus” screen being an expected sight when opening most modern titles.

It’s hard to understate how ahead of the curve Majestic was, giving gamers a glimpse into social online gaming years before that became the norm. It’s easy to imagine that Majestic would have been a much bigger deal if it had come out a few years later, as the public would be more open to the game’s format, story, and business model. Alas, it wasn’t to be. Like the conspiracies it focused on, Majestic remains a lingering series of questions with no easy answers.